Microbiome research has brought a unique perspective to the global problem of obesity. It seems that our eating habits, genomes, and lifestyle are not the only culprits in obesity: gut microbiome may have been holding the key to our metabolism and body weight regulation all along. Specifically, our current study suggests that weight loss surgery drastically changes the gut microbiome in both mucosal and luminal space in humans and subsequently alters the microbial metabolism of dietary or host-derived compounds, which may convey some of the metabolic benefits of the surgery.

The connection between microbiota and body weight has been increasingly studied in the last decade. In that time, researchers first observed differences in microbial communities in normal-weight versus obese individuals, and then followed these studies with animal models. In these models, fecal samples from obese humans or animals were transplanted into conventionally raised or germ-free animals. The results hinted a causality between microorganisms and obesity, in that the metabolism or phenotype of the receiving animals mirrored the microbiota of the donors.

In that vein, my Ph.D. lab at the Biodesign Swette Center for Environmental Biotechnology ( https://environmentalbiotechnology.org) delved deeper into the link between weight loss and microbes. In 2009, the lab published the first study on the microbiome of individuals that went through Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) surgery. This study demonstrated a drastically altered gut microbiome that is not similar to either normal weight or obese microbiomes (Zhang et al., 2009). Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, or simply “gastric bypass”, is a common bariatric surgery to induce weight loss in morbidly obese individuals. Gastric bypass has been also shown to improve metabolic comorbidities of obesity. This surgery limits food intake and absorption of nutrients by creating a smaller gastric pouch and bypassing the duodenum as illustrated below.

Later on, studies that monitored both humans and animals consistently demonstrated similar patterns in gut microbiome after bariatric surgery and convinced us that changes in the gut environment are reflected in the microbiome. Our previous report on gastric bypass surgery showed a greater abundance of microorganisms that are mostly associated with the oral cavity (Ilhan et al., 2017). However, our knowledge of microbiome post-bariatric surgery was limited to data gathered from fecal samples and there are still many gaps in the knowledge about gut metabolism that needed to be filled.

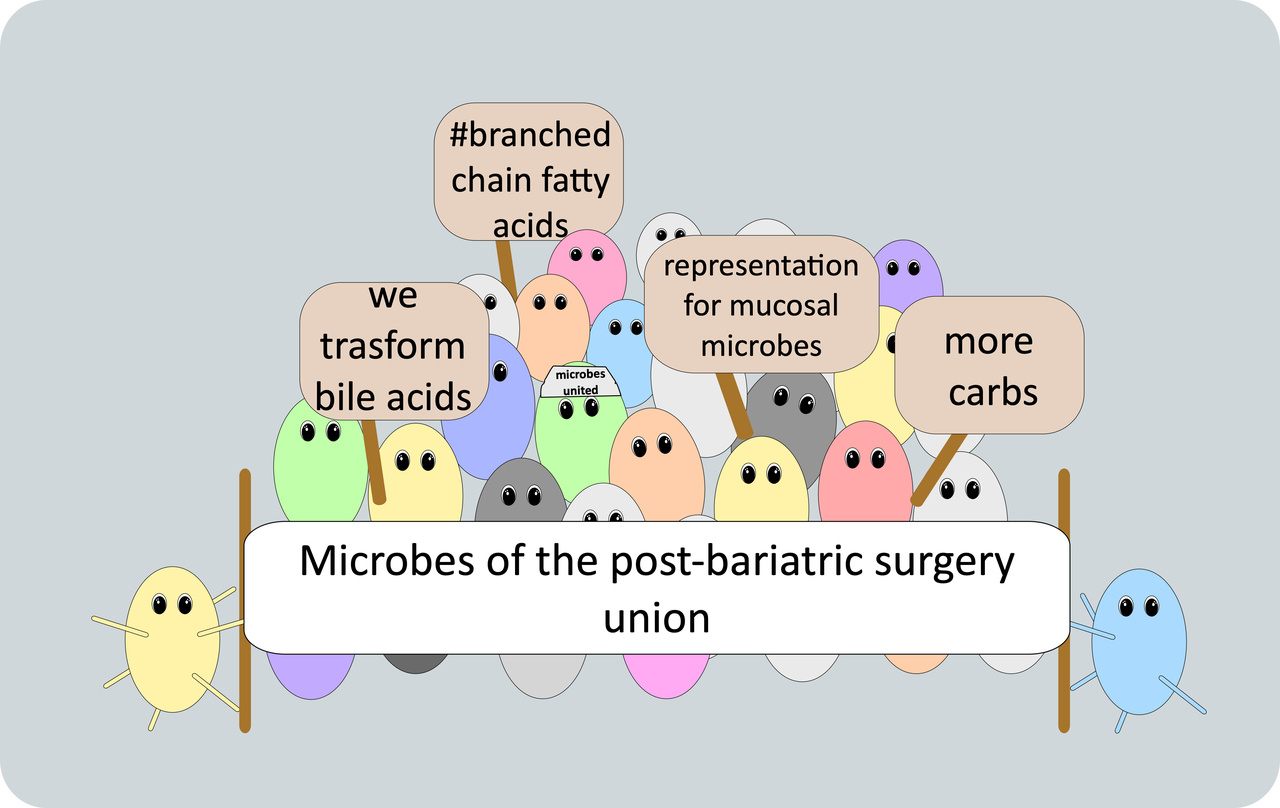

In the current study, in Dr. Krajmalnik-Brown’s laboratory at Arizona State University, in collaboration with Mayo Clinic and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, we longitudinally monitored gut microbiota (mucosal and fecal) and fecal metabolome of a morbidly obese cohort along with normal-weight controls. Accumulating evidence suggests that mucosal communities differ from fecal communities and they play an essential role in host immunity and gene regulation. Our analysis showed a significant change in mucosal communities after RYGB. For example, we observed an increase in the abundance of Akkermansia muciniphila, a known mucin degrader, in the rectal mucosa after RYGB. Notably, we observed a stronger and more consistent response of fecal metabolomes than microbiomes after the surgery. Amino acid fermentation was particularly enhanced and bile acids were detected significantly lower after the surgery. Our findings highlight that microbiomes along with their metabolic profiles are altered after bariatric surgery and can provide at least some answers to the metabolic benefits of bariatric surgery.

Find our paper at npj Biofilms and Microbiomes: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41522-020-0122-5

Additional references:

Zhang, Husen, et al. "Human gut microbiota in obesity and after gastric bypass." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106.7 (2009): 2365-2370.

Ilhan, Zehra Esra, et al. "Distinctive microbiomes and metabolites linked with weight loss after gastric bypass, but not gastric banding." The ISME journal 11.9 (2017): 2047-2058.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in